Modern art, art critics, and bad artists, are obsessed with the ‘new’. What else is there? Well, there’s the history of techniques, for a start …

Exhibition catalogue (→ PDF opens in new tab)

Riccardo Angelo’s art seems very accessible when he paints identifiable figures and poses, but inaccessible when his private thoughts and knack for surrealism take over the imagery. The theory, popular amongst critics of literature, that ‘the author is dead’ means that we do not have access to the intentions of artists. It is an idea that attempts to dislodge artists from the centre of their own work. It may be an effect of that dislodgement that art dealers—auction houses and galleries—encourage us to think of artists as in or out of fashion and, themselves, engaged in a struggle to stand for a while at the head of an advance guard. It is to everyone’s advantage that some artists appear to be at the cutting edge of taste, where investments will show a good return, and it is also completely irrelevant to the artwork.

Art criticism has a long list of well-worn words that are useful support critical claims to seriousness, and often before such claims to seriousness are warranted. Artists learn at art school and sometimes remain in the habit of obscuring what they know with what they learned.

It is a curious thing that the art world, the public language of visual artists, is saturated with artistic “intentions”. “What I mean by this is…” “In this picture I was trying to achieve…” “This is a painting about…” “So-and-so is trying to…” We lap up the intentions of painters in a way that we would find intolerable with, say, novelists.

However, I can not reconcile this effect with the knowledge that no artist I know talks to me about their art that way. (This, I have to admit, may simply show how I made the world I live in!) The more closely I get to know an artist, the less the conversation is about the apparent content and motive of the work than about the struggle to make it—about techniques, methods, materials, errors, frustrations and experiments.

This all amounts to saying that the artist’s history of art is very different to the art critic’s history of art. This is a fact worth noting. To an artist, the history of art is principally the history of the mastery of techniques and the struggle with materials: what is passed on, what is forgotten, what remembered, what can be seen or inferred from the surface of a painting and what must be imagined, what is discovered and what has to be re-invented, what he can do and what he cannot do. No-one who has spent any time with artists, listened to their conversations, and shared their practical daily concerns about their work, could deny that this is a basic truth about being an artist.

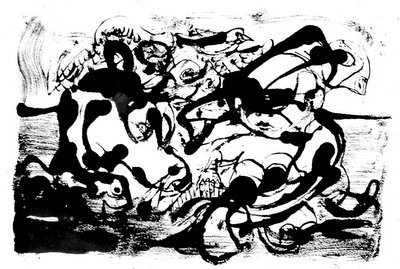

In this context, I think that Riccardo Angelo’s Nineteen monotypes exhibition was a litmus test of how to look at art, since its subject was not only the familiar figures that filled up the white space of the paper the monotypes are printed on, but also the technique itself. The nineteen monotypes were made specifically to draw attention to how they were made, and to the fact that the process of making them involved various, sometimes unexpected, stages of work.

The monotypes

Monotypes, as the name implies, should be one of a kind. Ink is applied to a plate that can be made of metal or glass, and may be flexible or rigid. The ink may be drawn on the plate; or painted on; or painted on, then rubbed and scratched off to make negative details. Plate and paper come together, sometimes, though not necessarily, in a press (a burnishing tool will suffice for some variations of the technique). The paper is peeled off the plate to reveal the image. The plate is wiped clean and the process starts again. Degas was a master maker of monotypes and he invented several distinctive variations of the technique, including making further images off the already used plate and hand-coloring the fainter second impressions. The beautifully luminous dancers’ tutus in Degas’ monotypes were made by first rubbing solid black ink on the plate and then rubbing away the ink with brushes and cloths to leave a blank area in the form of a white dress.

Riccardo Angelo’s nineteen monotypes were exhibited at a small, fine art gallery in Melbourne in September 2005. Angelo has made hundreds of these monotypes, usually in groups of about six to twenty. They are all organised by date. They do not have titles. The titles of the nineteen monotypes, taken randomly from superficially appropriate passages of the book of Genesis, were added to the monotypes at the request of the gallery director. The dates tell the viewer that some of the nineteen monotypes were made months before many of the others. Most, according to the dates, were made on a few days around the middle of December 2004.

First impressions: the meaning of ‘monotypes’

A monotype is one of a kind. However, the technique of making them encourages an artist to experiment with how the ink is applied and removed, repeating patterns, shapes and content in evolving sequences. Almost all monotypes are an instance of an evolving process and, of course, sometimes, failed prints are thrown away.

Many of the pictorial elements of the whole exhibition are in these first monotypes, made in August 2004. Birds. Wings. A squatting child. A snake. Two figures kissing. A figure kneeling, legs forming the shape of an inverted ‘V’.

In exhibition, the prints are not presented in any particular order. The first impression is confusing. Few viewers appear to spend more than seconds in front of each of the prints. You may look at the details of any print and become lost it its suggestiveness—the ‘drawing’ that forms the basis of the prints is apparently wild, undisciplined, free. Indeed, it is hard to imagine how it would be possible to control the materials to produce a fine effect: the viscous ink, brushes and glass are not ideal instruments with which to draw. Angelo is an excellent draftsman, but his abilities don’t appear, at first viewing, to be on show here.

It is only when viewing the prints from a distance and as a group that revealing patterns begin to appear.

Techniques and variations

Why do many of the monotypes present us with a figure that has fallen to its knees to form an inverted ‘V’ shape with its legs? Man, woman, dog, and creature—they are all the same—all reduced to the same pitiful position. The supplicant, bowed shapes of all living creatures in this world, Angelo seems to be saying, should tell us about something they all share. It is hard to pin down what he might be referring to. Most of the monotypes have some explicitly sexual content, but they are definitely not erotic. It is not even, really, a human theme. In the world of these drawings, man and dog suffer in the same way, men and women are equally exposed, and all nature becomes part of the muddled, expressive, psychological moment of the work and of the exhibition.

Then there are the groups of two or three monotypes that belie the individuality of the print process. It is clear from these prints that Angelo does not always clean the glass plate he uses before beginning work on the next impression. He reworks an image he has already made by making new layers of ink stick to the half-dried layers underneath, and he adds new details.

The monotype process produces unique prints, but Angelo has rediscovered something that Degas knew: the plate, whether flexible metal or inflexible glass (other materials can be used), becomes an anchor that keeps the work on theme. The plate remembers the structure and some of the details of the drawing, and always provides a useful departure point for the next drawing, if one is needed. The process itself is also telling us that the work is not random; not as random as we first thought.

These three prints demonstrate something different. Between one print and another the details may change dramatically, but the underlying structure of the picture can remain the same. On the right hand side of the three prints there is a group of trees, or a tree. On the left hand side: a much larger tree, a female figure (perhaps like a sphinx), and a child’s face with its mouth open, crying. Of course, there are birds, beaks, animals and snakes everywhere, making it difficult to see these figures. Look at the prints for a while and you begin to realise that deep patterns have repeated themselves.

The next two prints reveal another variation in the technique.

The second print is a reverse print of the first. This means that the second print must somehow have been printed from the first print, or the image reversed on the plate and re-printed.

What does it all mean?

One of the reasons I wanted to write about this exhibition, and why I wanted to publish a permanent record in print of these nineteen monotypes, is that it allows me to discuss an unresolved question about the relationship between artists and their critics. I include in ‘artists’ all kinds of artists, though I realise that, increasingly, it is used to refer only to visual artists.

So much of what one reads about art is shallow, ideological or self-serving. Is there an appropriate way to write about art at all? I’m not really sure. I would align myself with Susan Sontag, if anyone. I am not interested in producing another interpretation, but in what I see and in transmitting some of that excitement about what is visible.

This is, itself, a philosophical manoeuvre, of course. An ‘interpretation’ cannot avoid being, at some level, an attempt to master and comprehensively remake the art it is talking about. Interpretations come to stand for the works of art themselves. There is nothing intrinsically wrong about that. In fact, in life as in art, an interpreter is exactly what we need sometimes.

However, it is undeniable, I think, that certain critical ‘positions’ or theories seek to remove artists from a privileged relationship to their own work. The effect is strange. The public discussion of art is carried on as though art itself were an ‘effect’ or by-product of the history of ideas. Artists are made to line up while an -ism is pinned to their lapels. At some point the unreality of it may strike you as itself meaningful.

Riccardo Angelo’s Nineteen monotypes exhibition invited us to view ourselves in the act of looking, and to notice how many of the artist’s intentions and meanings could be traced from one moment to the next.

You must be logged in to post a comment.